Emotional Self-Regulation

Life continuously exposes individuals to potentially arousing situations which have the potential to trigger an emotional response. These situations can be:

- external (i.e. when you receive criticism or a compliment, see a new born baby or witness another person suffer)

- internal (i.e. when you think negative or positive thoughts about yourself or think positive or negative thoughts about your future.

Whether a potentially arousing situation triggers an emotional response or not in an individual depends upon the amount of attention they pay to the situation, as well as their cognitive (mental) appraisal of the situation including the meaning and significance they ascribe to the situation and the level of confidence they have in their ability to deal with the situation.

The strength, intensity and duration of an individual’s emotional response however, depends upon their emotional sensitivity and their ability to self-regulate.

An individual’s emotional sensitivity and their ability to self-regulate is influenced by:

- whether or not they have been getting enough sleep, eating well, exercising and participating in stress relieving/relaxing activities, etc.

- their executive function capacity which influences their emotional impulsivity (the likelihood of a primary emotional reaction occurring in response to a stimulus, as well as the speed of the emotional response) as well as their emotional control/inhibition competence

- their habits or habitual responses.

The fight or flight response

An emotional response can be described as the behaviour and physiological expression of feelings that an individual displays in response to a situation they perceive to be personally significant (Gerrig & Zimbardo, 2002).

The behaviour display by an individual when emotionally triggered (their facial expressions, eye contact, body movement and verbal expression i.e. tone of voice, volume and language, etc.) is influenced by the internal physiological changes that take place in their body as a result of their fight or flight response being triggered.

The fight or flight response is an instinctual protective mechanism. When triggered an individual’s:

- heart rate and blood pressure increases

- peripheral blood vessel constrict in order to divert blood to the heart, lungs and brain

- pupils dilate to take in more light

- blood-glucose level increase to provide their heart, lungs and brain energy

- muscles tense up, energised by adrenaline and glucose

- smooth muscle relax in order to allow more oxygen into the lungs

- nonessential systems (like digestion and immune system) shut down.

The individual will also experience trouble focusing on small tasks and will loose the ability to use their executive functions (which further reduces their capacity to regulate their thoughts, words, actions and emotions) when their flight or flight response is triggered. This is because the brain goes into attack or escape mode.

The fight or flight response can be triggered by both real and imagined danger. Problems can occur if an individual’s flight or fight response becomes triggered too easily or too frequently in response to perceived but imagined danger.

Emotional regulation

An individual’s emotional response can be healthy or problematic in that it can have a positive or negative affect on goal attainment, social relationships, health and wellbeing. For example, experiencing and expressing emotions such as love, happiness, joy and empathy can serve to create, maintain and strengthen interpersonal relationships with others. Whereas experiencing and expressing emotions which are considered socially inappropriate such as anger and aggression can harm or destroy interpersonal relationships and result in social isolation.

In order to enhance or subdue an emotional response and thereby protect goal attainment (as well as social relationships, health and wellbeing), individuals rely on their emotional self-regulatory skills.

Emotional regulation can be defined as the automatic (unconscious) or controlled (conscious) processes involved in the initiation, maintenance and modification of the occurrence, intensity and duration of an individual’s emotional experience and expression.

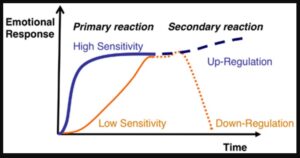

According to the Hypothetical Model of Emotional Sensitivity versus Emotion Regulation developed by Koole (2009), the process of regulating one’s emotions contains two distinct stages.

Hypothetical model of emotional sensitivity versus emotion regulation. From Koole (2009).

Koole (2009) termed the first stage primary reaction. During this stage, an individual experiences (and often expresses) an immediate raw emotional response to a situation.

The intensity and speed in which a primary reaction occurs is determined by an individual’s emotional trigger sensitivity (see above).

Following this primary reaction, Koole (2009) asserts an individual can modulate and change their emotional reaction in order to ensure goal attainment and maintain their interpersonal relationships. The resultant emotional response is termed secondary reaction.

The steps involved in modulating and changing one’s primary emotional response include:

- attaching a reward (which provides the motivation) to the effort of reducing/modifying one’s primary emotional reaction

- engaging in self-regulatory actions to actively reduce/moderate the primary emotion (i.e. speaking to one’s self in order to self-soothe, refocusing attention away from a provocative event)

- using working memory, problems solving (including forethought to predict future outcomes of possible responses) and planning skills to organise the eventual secondary response so that the secondary emotional reaction is adaptive and supportive.

Emotional dysregulation and ADHD

The prevalence of emotional dysregulation amongst children diagnosed with ADHD is estimated to be between 24-50% . In adults diagnosed with ADHD, the prevalence of emotional dysregulation is estimated to be around 70% (Shaw et al., 2014)

Individuals with ADHD often experience difficulties regulating their emotions. These challenges are thought to have the greatest impact on an individual with ADHD’s wellbeing and self-esteem, far more that the core symptoms associated with ADHD (hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention).

Emotional dysregulation can be defined as an inability to modulate one’s emotional experience and expression, which results in an excessive emotional response. This excessive response is considered inappropriate for the developmental age of the individual and the social setting in which it occurs.

ADHD related emotional dysregulation is thought to result from poor executive function control which contributes to an individual having (Barkley, 2015):

- Highly volatile emotional trigger sensitivity and emotional impulsivity due to poor self-restraint. Emotional impulsivity contributes to ADHD symptoms such as impatience and low frustration tolerance, quickness to anger/reactive aggression/temper outbursts, and emotional liability.

- Problems self-regulating their primary emotional response. Individuals with ADHD can experience such intense, overwhelming primary emotional reactions that they find it difficult to inhibit the expression of this emotion or to moderate the emotion and replace it with a secondary emotional reaction.

- Problems refocusing their attention away from strong emotions. An inability to refocus attention away from strong emotions can make it difficult to reduce or moderate a primary emotional response. Refocusing problems can also contribute to thought rumination.

- Difficulties self-soothing in order to moderate their primary emotional response due to poor working memory (i.e. reduced ability to use self-speech and visual imagery).

- Difficulties organising and executing an appropriate secondary response due to difficulties appraising, flexibly manipulating and organising information; generating and appraising alternative responses and their possible outcomes; and planning an appropriate response.

As a result individuals with ADHD are more likely to:

- experience and display emotions more intensely particularly during interpersonal interactions – possibly due to being overwhelmed by the emotion

- become overly excited

- focus on the more negative aspects of a task or situation

- express frustration or anger and become verbally or physically aggressive

- experience problems in social relationships including social rejection, bullying, and isolation

- experience relationship and marital problems, relationship breakup and divorce

- have difficulties achieving work or academic goals/requirements, receive a school suspension or expulsion, lose their job or fail to be promoted

- be involved in road rage and car accidents

- report increased psychological distress from their emotional experience

- develop anxiety and/or depression

- have conduct problems, be involved in crime and be institutionalised.

Emotional dysregulation and parenting stress

Children with ADHD have been shown to significantly increase the amount of stress experienced by parents. This is further increased when the child has emotional regulation problems. Parents who experience extreme levels of stress may suffer psychologically and may therefore be less able to implement the types of interventions required to help their children (Theule et al., 2011).

Using effective parenting strategies when caring for a child with ADHD can help to decrease the stress parents experience, as can attending parental support groups and participating in self-care.

References

Barkley, R.A. (2015). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment, 4th ed. New York: Guilford Publications.

Gerrig, R. J., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2002). Psychology and Life, 16th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Gross, J. J. (2007). Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford Press.

Gross, J. J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J.Gross (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regulation (pp. 3-24). New York: Guilford Press.

Jonson, C.A. (2017). The Relationship between ADHD and emotional regulation and its effect on parenting stress – Thesis. University of Louisville. Retrieved from http://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors/144

Koole, S.L. (2009). The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review’. Cognition & Emotion, 23: 1, 4 — 41.

Nicholson, A. (2017). Calming the Tide: Emotional Regulation in Young Adults with ADHD – Thesis. University of Calgary. Retrieved from http://theses.ucalgary.ca/jspui/bitstream/11023/3614/1/ucalgary_2017_nicholson_andrew.pdf

Shaw, P., Stringaris, A., Nigg, J. & and Leibenluft, E.(2014). Emotional dysregulation and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3): 276–293.

Surman, C., Joseph Biederman, J., Spencer, T., Yorks, D., Miller, C., Petty, C., & Faraone, S.(2011). Deficient Emotional Self-Regulation and Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Family Risk Analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(6), 617-623.

Theule, J., Wiener, J., & Rogers, M. (2011). Predicting Parenting Stress in Families of Children with ADHD: Parent and Contextual Factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies.

Van Stralen, J. (2016). Emotional dysregulation in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 8(4), 175–187.

Voss, K.D., & Baumeister, R.F. (2011). Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory and Application, 2nd ed. New York: Guildford Press.